Conversations and Community

Author: Scott Barksdale

Posted by Alythea

Sometimes I’m lucky enough to overhear a conversation that fits a question I’ve been carrying around. Maybe due to my sense of murkiness on the topic, I’m drawn to listen but reluctant to join. If I’m really lucky, the conversation helps clarify my thinking, and the people I happened upon have left me with something helpful, something useful.

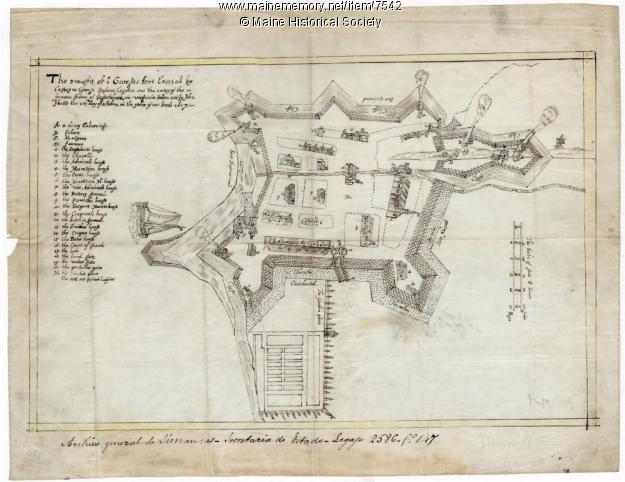

This happened to me earlier in the school year. My 4th graders had been studying colonization by looking closely at a 1607 map of an English fort on the coast of present day Maine. I had been feeling unsure about what things to tell them about the map and what things to leave for them to discover. It seemed that each detail I had decided to tell – that this English map had been discovered in Spanish archives, for example – overshadowed their own ideas about this document, as if I were somehow more authentic than this map. It was only October after all, and my students were still getting used to critical exploration and to the hard work of developing their own ideas.

On this particular day, my students had just noticed the words “Pars Oriental” and “Occidental” written in small, careful letters. They found the first on the top of the map, written just above the fort’s wall, and the second on the bottom. When I had taught this unit in years past, I decided not to tell students that these words were the equivalent of east and west. There were many words on this map that students did not understand, and if I began explaining one, how could I not explain another?

But these words now seemed different. Since we were also working with a satellite image from Google Maps that included the area on this hand-drawn map, orientation would be a powerful tool for connecting these two primary sources. In addition, we were reading a third source written by the ship’s captain who had transported these Englishmen to North America, and I wanted my students to be able to readily apply his words about building the fort “on the West Syd of the Ryver beinge almoste an Illand of a good bygness” to all three documents. So while I wanted to follow my students closely as they thought their way through the learning territory in these primary sources, I also wanted to do something that seemed a lot like leading them to a promising vantage point. Since critical exploration is about helping students develop their own ideas, I felt conflicted by the thought of introducing this ready-made idea of orientation.

It was the weekend after this class that I happened upon just the right conversation for my predicament. We were taking a break during a Critical Explorers meeting, and Alythea (our director) was talking with someone about the critical exploration she had recently led us in of a painting from the Slavery and Reconstruction unit. She shared that when she and the collaborating teacher taught this in a middle school class, the students had asked if the artist was black or white. She had to decide whether to tell them, or whether to pass the question back to them, preserving the opportunity for them to assemble their own thoughts and theories about the artist’s race.

While her situation was not identical to my own – she was teaching older students about a very different topic – her question, in many ways, was. Deciding what, when and how much to tell students about a primary source is a common challenge in critical exploration. Do I share something I know about a primary source’s background? If yes, do I share it in the beginning or at some other time? Maybe I share something about what students have not yet noticed, maybe I wait to share until they have found it through their own examination. Or, do I simply not tell them anything at all? I’ve found that the less I tell students, the more they seem to hang on to each thing I add or underscore. This is a constant reminder to me of the need to be purposeful with what I decide to tell.

As I continued to listen in on the conversation, Alythea spoke about a critical exploration she and Eleanor Duckworth had once adapted for Eleanor’s course. The class would be studying some historic objects. While there would have been much for students to learn through figuring out that these were butter molds from the 19th century, further exploration would then be limited by how much class time might be left. So, because they wanted students to spend the class time exploring a learning territory beyond questions of what the objects were and when they were from, they decided to answer those questions at the start. The exploration that followed confirmed their sense that telling students something can sometimes lead to more exploration.

For me, this was a helpful idea. Critical exploration has been described as a kind of teaching where students do the telling and teachers do the listening, but it is important for me to remember that it is also one where I need to purposefully define a learning territory. I had done this through carefully choosing the map and the other two primary sources for my students to study, and I now realized that I could further define it by deciding what to tell them about these documents.

This kind of telling, however, takes a different shape from a traditional lesson or lecture. While I might at some point decide that explicitly teaching about the idea of orientation could be a productive move, my job while leading my students in a critical exploration is to stay on the heels of their thoughts and ideas. I help them develop and clarify their thinking in whatever way I can – by asking them to say more, by telling them when I don’t understand what they mean or how one thing makes them think another, by making space for their quieter voices. To avoid the trap of telling my students what they ought to think (“North faces up!”), I give them another thing to think about in addition to the map – word meanings, in this case. Telling my students about the idea of the map’s orientation would likely overshadow their thinking because it is someone else’s idea and not yet their own. However, simply telling the meanings of these three words would open a new and complex set of possibilities for them to explore.

So, I began the next week’s class with just a sentence about “Pars Oriental” and “Occidental” meaning east and west. As one student’s idea of rotating the map 90 degrees clockwise (moving “Occidental” to the left side) slowly filtered through the class, I watched the idea of orientation begin to take shape in their thinking. I felt fortunate to have overheard such a helpful conversation at our meeting.

In much of life, the communities of people that we happen upon determine the conversations we overhear. Online, something different seems to be true, with conversations opening the doors of community. While the topics and students we teach may be different, our teaching and the ensuing conversations have much in common. It is our great hope that criticalexplorers.org becomes a place to be among the conversations of a community of teachers, thoughtful conversations to which all can listen and any can join.

Scott Barksdale serves on the Critical Explorers Board of Directors.

Thanks for your comment, Corey. Like you, I am curious about how others negotiate these tensions. It would be great to hear other voices on this!

I’m finding some of the common ground you’re looking for in your idea of a “teacher define[ing] a space that is relevant to what the student will be tested on” and that then “students will steer their own learning but in the process will also get what they need to be successful on the standardized test.”

Here are some thoughts:

– On the curriculum side of things, that “defining” would seem to be very much about thoughtfully picking the things (primary sources, etc) we ask our students to look at. For me, district and state standards play a central (and helpful) role as I decide on what materials to pick. Also, I often think about this selection process by asking myself “what do I want students to think ABOUT”, as opposed to “what do I want my students to think” (which would seem to fit in your “narrowly defined knowledge” category).

-On the teaching side of things, I’m thinking about how much I am involved with steering my students’ learning. Yes – they notice, they wonder, and they have ideas about what they wonder, but I often decide what questions of theirs we will spend our class time exploring (after my class did its noticing and then wondering about the above map of for St. George, I said something like, “Let’s start with X’s question”). Also, I often need to make a call about what comments to push for clarity, and what thoughts to put next to each other (“Is your idea similar to what X was saying?”) So, the “steering” of this exploration comes from both the learning and from the teaching, from my students and from me. If time limitations were not such a huge factor, I might approach this differently.

-One of the arguments I’ve heard against spending time this way in the classroom is that it takes time away from learning other stuff -breadth vs. depth. While I think there is a strong argument to be made for favoring depth over breadth, in situations where “coverage” is the dominant force, I’ve found that I can make at least a little space for critical exploration. I’ve experienced this mostly in math (my district uses Everyday Math, which is not an inquiry based program). About every 2 to 3 weeks, the program has something called an “Open Response”, which is an assessment that calls on students to explain their reasoning on one extended problem. After students have taken the assessment, we will often spend the second half of the class (or first half of the next class) doing a critical exploration of the problem. Students use their correcting pencils for this, so it is clear what work was done on their own, and what thinking happened after our group work. So, in this context, critical exploration becomes one of several teaching methods I end up using. It is not the way I’d prefer to do it, but I am able to squeak it in, and I’ve seen it benefit students (even on standardized assessments!).

-Another way I squeeze critical exploration-inspired learning into these coverage-inspired math classes is during the daily homework routine. Instead of me just collecting homework or sharing the answers or opening space up for questions, I have students check their homework against each other. We call it “reconciling” their homework. If they have different answers from their partner, they need to reconcile them by explaining to each other how they were thinking about them. Student often end up looking up words in the glossary, checking algorithms. If they are unable to agree, we talk about it as a class. It can to 5 to 10 minutes, and is a neat way to bring student thinking (instead of simply “the answer”) to the center of the discussion. This might be different from a full-on critical exploration, but it has many of the elements and many of the benefits. These kinds of daily routines are short, but they have a great cumulative effect and reinforce great habits of inquiry. If you’re not already familiar with it, a neat book about this sort of thing is Bob Strachota’s “On their side”.

-In the critical explorations I do with my class, I am sometimes comfortable with adding something to the conversation, but only AFTER students have had the opportunity to develop their own ideas. So, if someone fumbles with something like Popham and Jamestown existing before Plymouth, for example, I might interject something like, “You need to know that this was in 1607, and that was in 1620.” I might do this anyway if there was confusion, but especially if it is the kind of thing that may show up on an assessment. Also, I’m sometimes comfortable sharing an outside idea about what we are studying. With the unit on early colonization the above map is from, one of the state and district learning goals is to be able to articulate why some colonies survived and others didn’t. Even at the end of our section on the Popham Colony, the general idea of leadership of a colony had not entered the class discussion (though noticings like “the president died” and “the person who took his place decided to go back to England to collect his inheritance” did). I gave what I guess you could call a mini-lecture, couched in terms like, “Some people also think that a lack of leadership…”. What makes this consistent with critical exploration, I think, is that I couch it in terms of “other people’s ideas are this…” (instead of “One reason the colony failed is this…”). Also, whenever we look at a secondary source or an outside idea like this, I always emphasize that the people who came up with them were looking at some of the same primary sources that students we were looking at, leaving them open for students to disagree with based on evidence they’ve seen. So I’m always trying make clear that any “authority” of these ideas originates in the primary sources, not from some inherent “rightness” of the idea.

One final thought: there are many standardized tests where students need to think critically. I’m thinking about things like DBQ’s (Document Based Question on the NY Regents, AP exams and others), and essay answers (“constructed responses”) where students need to take a position on something and support it. A breadth of knowledge is always necessary for these, but to do well on them, students need to be able to also express a depth of understanding (at least about some of it!) and be able to think critically about the sources of that knowledge and how it supports their broader ideas. So in many ways, I do not see a conflict between spending time on depth through critical exploration and wanting kids to perform well on standardized assessments.

I’m curious about how have others negotiated the reality of standardized tests and state learning goals, and used/incorporated critical exploration into a coverage-oriented curriculum. Thanks again, Corey, for your comment!

Scott

Corey Brooks

Thanks for the thoughtful post Scott. Next year I will be teaching in Baltimore City and I fear that my philosophical leanings will be overcome by test pressures and a mandate to hit learning targets in short periods of time. I’m wrestling with ways to have my cake and let the public school bureaucracy eat theirs too. My primary concern is the high stakes tests for students that do not value critical exploration and the accountability measures for teachers based on those tests.

I wondered if some common ground exists between critical exploration and the sort of narrowly defined knowledge that is valued by standardized tests when you said you need to “purposefully define the learning territory.” If the teacher defines a space that is relevant to what the student will be tested on, but makes the space broad enough for the student to play in many directions, and does not set pre-determined goals about what they must find within that space, perhaps students will steer their own learning but in the process will also get what they need to be successful on the standardized test? I think it’s natural to get broad coverage when you have a group of students with various thoughts and interests and experiences, and each individual provokes the others to explore ground they otherwise might not have chosen when confined to their own brains. Yet in the back of my mind remains a fear that if I allow students this much freedom, they may not hit the narrowly defined areas that are valued by these tests. And if they don’t will I be tempted to intervene?

I would love to hear from you Scott or other who have navigated these tensions in a public school setting. Thanks!

Corey